Interview with Irish Artist, Aidan Harte: “Public sculpture is an opportunity to work big, something that all

sculptors crave.”

Aidan Harte, the man responsible for the most widely-discussed artwork in Ireland this year, talks art, Irish mythology, and the influences of his infamous sculpture Púca.

Earlier this month, a public artwork commissioned for a town in Clare became the focus of a national news story. The piece is entitled Púca, and offers a striking, contemporary depiction of the horse-headed chancer from Celtic mythology. It was due to be installed on the streets of Ennistymon, but after protestations from a local parish priest, Clare County Council paused the project. It is currently under evaluation, and has energized a vibrant debate in Munster and beyond. Is it a paganist symbol unsuited to be public art, or a loving tribute to our island’s rich cultural history?

To better understand the situation, we sat down with Dublin-based artist Aidan Harte, the man responsible for the most widely-discussed artwork in Ireland this year.

Tell us about yourself.

I’m from Kilkenny. I began in animation, directing Cartoon Saloon’s first TV show. It won an IFTA. Following that, I studied Classical Sculpture in the Florence Academy of Art. I returned to Dublin ten years ago and began sculpting. My bronze sculpture can be found in Sol Art Gallery on D’Olier street, Dublin.

Tell us about your art practice.

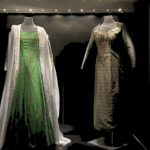

My ambition was always to bring to life disreputable characters like the Minotaur and the Púca, To do that, I had to become an accomplished figurative sculptor. I studied drawing and anatomy in Florence. The Old Masters’ subject matter influenced me as well as their techniques. Characters like the Centaur and Minotaur embody, I think, humanity’s duality. The anthropological term for these hybrid figures is a “therianthrope”. They reappear in the hunting scenes of cave paintings all over the world. Whatever instinct made our ancestors create art, made them create human figures with tails or beaks, or heads of lions or bulls. I guess it made me make Púca.

What made you want to pursue this project? And tell me how you began.

Public sculpture is an opportunity to work big, something that all sculptors crave. The Púca is two meters tall, by far the biggest sculpture I have made. Ennistymon is a pretty little town near the Atlantic coast in County Clare, a part of Ireland known for its traditional music. The horse fair of Ennistymon was once famous, and I connected that to the Púca, a shapeshifter who often appears in the form of a horse.

Making statues is a unique practise. Lots of preparation work is imputed. How has the pandemic affected the sculpting process, from studio work to casting?

It has had little effect on me – I was working in my studio through the last lockdown. It interrupted my foundry more so. They had to delay casting of several pieces, and so that will have delay other projects in turn. I understand that gallery sales have not been hurt hugely either. Other industries have been hit worse.

Irish mythology has some great representation in statuary, like The Children of LÍr in the Garden of Remembrance or the Taín pieces by the IFSC building. What made you choose the Púca to add to this public art tradition?

Oisín Kelly made The Children of LÍr and similar art in the 60s and 70s, the last great flowering of Irish interest in the Celtic past. Then followed a dreary period where anything too Irish was considered kitsch, but that cultural cringe is now itself old hat. Folklore is mythology’s disreputable brother. I’ve loved those stories all my life. They have been given new life by magic realists like Angela Carter and Neil Jordan. That’s what I want to do with the Púca who, contrary to what you may have heard, is not a devil. He’s more akin to the Greek Pan, and English Puck – a wild nature spirit. The fairies in Irish folklore were spirits who were not good enough for heaven and not wicked enough for hell. Just like us, they are conflicted and unreliable.

Were there any specific influences that helped you envision this piece?

The Discobolus of Myron has a similar pose, and the terrifying horses of the Elgin Marbles, with their rolling eyes and lolling tongues, were another classical inspiration. More recently, I like the élan and audacity of Barry Flanagan’s Nijinski Hares. My Púca is another dancing fool.

You capture Púca‘s mischievous side wonderfully. Were there specific texts you studied?

Thank you. The Púca is a Celtic cousin of Shakespeare’s Puck, a lord of misrule associated with carnival. Irish artists, from Lady Wilde to Flann O’Brien, have constantly reinvented this dark horse. His hoofprints are found across Ireland, at Carrigaphooca Castle in Cork, the Puck Fair of Kerry, and Ahaphuca in Limerick. Poulaphuca in Wicklow is famous. But there’s another Poulaphuca in the Burren and anyone who has left the Léim an Phúca Mhóir or seen the Wedge Tomb of Caheraphuca knows that the Pooka is a frequent caller to Clare. Westropp’s A Folklore Survey of County Clare tells of a Clonlara man who becomes the Pooka’s sport. UCD’s Folklore Collection reports that a Kilkee man suffered a similar fate.

“The Púca is a shapeshifter as you know, and I suppose the story has completely changed shape since it began to rumble in April.”

Clare County Council have put the project on pause, following condemnation from the local priest. The peculiar controversy seems to have created growing support from Clare residents, who are speaking up in favour of your piece. Are you hopeful that community support will help Púca reach that unveiling day?

The funny thing about the objections is that no one has actually seen the sculpture. They have only seen photos. I finished the clay on schedule in March. Bronze Art Foundry in Dublin made the mold for me in April. Before casting could begin in May, the project was paused. If we get the green light next month, it’s just a matter of pouring the bronze. My foundry, as you can imagine, was disappointed with the delay. Naturally I was too, but Clare County Council’s decision to pause was sensible.

The intervention of celebrities like Dara O’Briain, Chris O’Dowd and Maeve Higgins obviously played a part in the shift. It also helped that everyone got to see the picture from my studio where the scale could be properly appreciated. Local politicians and clergy have every right to speak up for their constituents and congregation, but now everyone knows that the Púca is only a rogue and nothing sinister. Since last week I’ve heard that CCC has been deluged with support so the scale is now more balanced.

The Púca is a shapeshifter as you know, and I suppose the story has completely changed shape since it began to rumble in April. We shall see.

This work was commissioned especially for Ennistymon. If the censorship campaign is successful, are there plans to potentially relocate it?

Art rarely intrudes into Ireland’s public consciousness – but last week the Púca was trending on twitter. Since the story went viral, several credible offers have come in. He will find a home. The only question is where.

What other sculptures would you like to make in Ireland?

I’m spoiled for choice! Irish mythology and folklore are populated with wild characters. I’ve always thought Balor of the Evil Eye, the tyrannous Fomorian giant, and his heroic grandson Lugh of the Long Arms, would make a great pairing, an Irish David and Goliath.

To contact or learn more about Aidan Harte’s work follow him on social media and check out his website:

Instagram: @aidanhartesculptor | Twitter: @harteaidan | Website: www.aidanharte.com

![Conversation with Maser: “I found graffiti definitely was the vehicle for me to be able to really explore what I wanted to do, meet similar peers that had the same sort of mindset as me […]”](https://dublinartlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/DAL-Interview-4-391x260.png)